Living a debt-free life : Utopia or realistic aspiration?

29 April 2020

Recent surveys indicate that the biggest aspiration of millennials today is not to buy a house or to get married, but to become debt-free (e.g. Business Insider, New York Life). In the US and UK, many young adults are struggling with enormous student loans, but even in countries where studying is cheaper similar echoes are heard.

Millennials want to become more flexible in their life-choices, having more freedom to change jobs, houses, etc. They have seen their parents being restricted in certain life choices by the debt they carried along. Nonetheless a debt-free life is probably more an utopia than a reality.

Almost all economists agree that debt is something positive, when properly used. Debt helps you meet your goals and take life to the next level. Debt can however also destroy you. But when managed responsibly, it brings many advantages:

- It allows you to invest in choices, which can generate more revenue than the interest you pay. For example a mortgage for a house of which the value appreciates, can result in a great profit. The same applies for student loans, as a diploma is the best way to increase your salary.

- Loans can be cheap. For certain loans like mortgages, student loans, loans for eco-friendly cars or green renovations, …, interests are often fiscally deductible, making it more interesting to use debt rather than savings. But even if not fiscally deductible, loans can still be a cheaper alternative, especially with current low interest rates.

- Loans can bridge short-term liquidity gaps. Instead of having to continuously keep a large cash buffer in liquid saving products (most banks suggest to keep 3 to 6 times your monthly salary in your savings account), it is often better to invest long-term and use debt to bridge short-term liquidity gaps. Especially with products like Capilever’s LABL, which allows to get low interest rates even for short-term credits without object by blocking some of your investments.

Even though these arguments are strong, decisions are often taken emotionally and not rationally. If millennials have a more negative sentiment towards debt than previous generations, then banks should not ignore this.

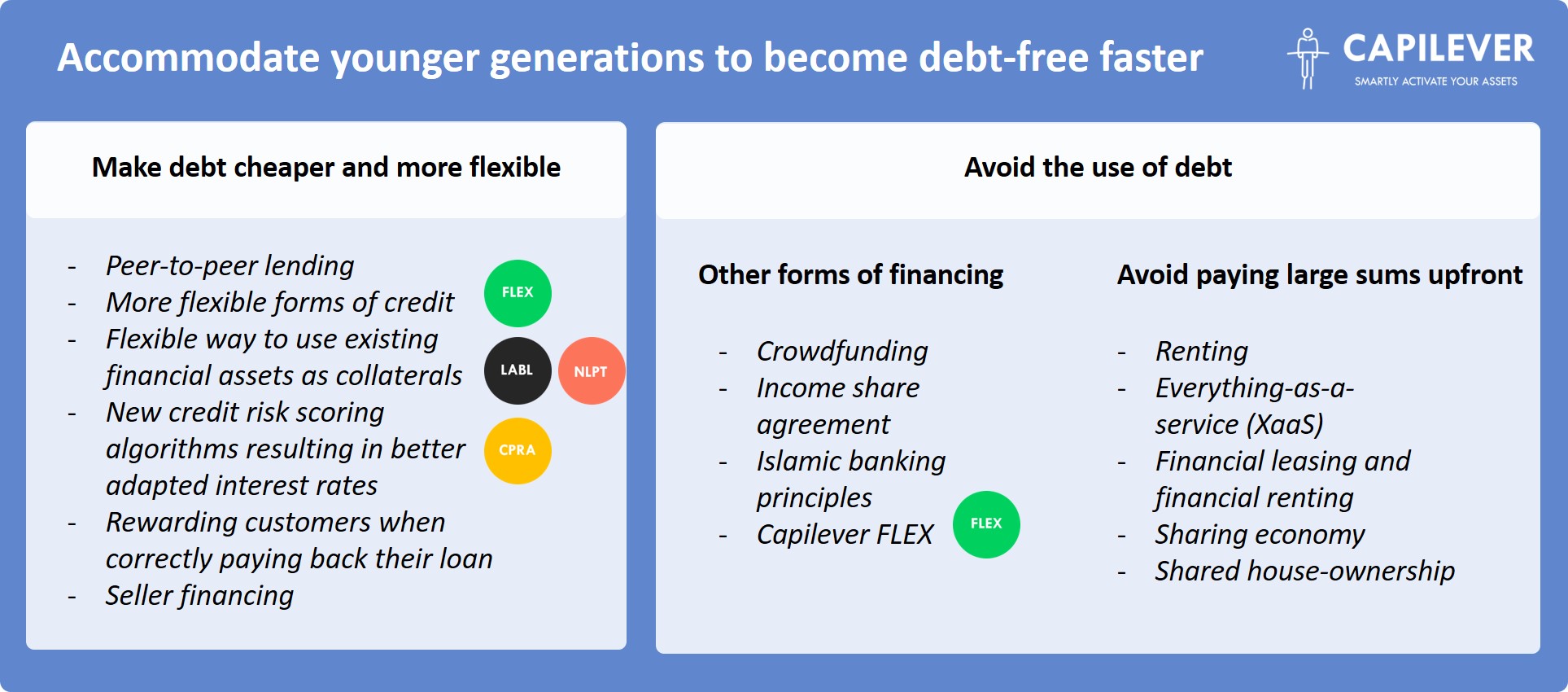

Two actions can be taken to accommodate the sighs of millennials to become debt-free faster:

- Make debt cheaper and more flexible. Many initiatives in the financial sector are being taken for this, e.g.:

- Peer-to-peer lending: one of the most popular categories of Fintechs are the peer-to-peer lending platforms, such as LendingClub, FundRise, Funding Circle, Prosper… By bringing borrowers in direct contact with investors, these platforms aim to provide lower interest rates for borrowers

- More flexible forms of credit, for example allowing customers to change the reimbursement amount and duration of their loans at regular intervals

- Flexible ways to use existing financial assets as collateralsfor credits, e.g. the LABL product of Capilever

- Rewarding customers when correctly paying back their loan, e.g. when customers have correctly reimbursed their loan, they don’t need to pay the interests of the last 2-3 months of the loan

- New credit risk scoring algorithms, which are not only based on financial information, but also on other sources of information, allowing to get a better view of the risk profile of customers and in many cases resulting in better interest rates

- Seller financing: this instrument can be used by buyers with difficulties to obtain a mortgage. In this setup, the buyer repays the existing loan of the seller, meaning he pays the seller every month (who repays the existing mortgage), rather than reimbursing his bank for a new mortgage.

- Avoid the use of debt. This can be done in two ways: either the financing is handled by another form of debt, either byavoiding to pay large amounts upfront to acquire a good or service.

- Another form of financing: also on this front a number of initiatives have already been taken. In many cases, a sort of debt vehicle is behind the product, but presented in another way, changing the psychological impact for end-users.

- Crowdfunding: via crowdfunding, companies or individuals can raise money, by attracting a large number of small investors. Platforms like Indiegogo, Patreon, GoFundMe, Kickstarter, Kiva, …, bring together investors and borrowers. Crowdfunding can result in a debt product, but usually crowdfunding works reward or equity based.

- FLEX product of Capilever: this product, which under the hood combines a long-term investment and debt product, allows customers to set a number of fixed slots to receive or pay a specific (indexed with inflation) amount of money. This way, the product offers a way to balance out fluctuations in a household’s budget (both at income and expense side) in a very easy and flexible way.

- Income share agreement: in this financing structure, an investor (can be a bank) provides a sum of money to a recipient, who agrees to pay back a percentage of their income for a fixed number of years. This type of financing has become popular as an alternative to traditional student loans.

- Islamic banking principles: in Islamic banking all banking activities need to comply with Sharia, which prohibits to invest in goods or services contrary to Islamic principles (e.g. gambling, alcohol, smoking, …), but also to charge interests on loans. In order to buy a house in Islamic banking, usually a financing structure called Murabaha or cost-plus financing is used. In this setting, the customer of the bank asks the bank to purchase the house on their behalf, after which the bank sells the house to the client (via monthly repayments) with a profit charge.

- Avoid paying large amounts upfront: people can also try to avoid buying expensive goods or services (like a house, a car…), which result in the creation of debt. In corporate terms, this is called transforming capital expenditures (Capex) into operating expenses (Opex). Some examples of common practices are:

- Renting: the most classical way of avoiding large capital expenditures, is by renting a house, a car…

- Everything-as-a-service(XaaS): many goods and services are no longer bought as a property, but instead consumed as a service (i.e. replacing ownership by a subscription model). Typical examples are cloud computing (instead of buying expensive hardware), mobility as a service (offering subscriptions to bike, eStep and car sharing), PC as a service…

- Financial leasing and financial renting: often used for buying a car, these practices allow to lease or rent the car from a financial institution. Often these contracts not only include the usage of the object (car), but also other services like for example its maintenance, car assistance, … The difference with renting is that in financial renting, the bank acts as a financial intermediary, so the customer is not directly renting from the rental company.

- Sharing economy: new digital platforms facilitate the sharing of infrequently used, expensive goods (such as machinery, electronics…). These platforms also remove the acquisition cost of these expensive goods.

- Shared house-ownership: via this product, a person only buys between a quarter and three-quarters of a property, with the option to buy a bigger share in the property at a later date. Purchasers pay rent to a housing association for the remaining part of the property that they don’t own. New platforms like e.g. Wayhome also find investors to buy the remaining part of the property. New PropTech companies are further developing this mechanism, via digital tokenisation, which allows to divide the ownership of the house in much smaller parts, making the product more flexible and frictionless.

- Another form of financing: also on this front a number of initiatives have already been taken. In many cases, a sort of debt vehicle is behind the product, but presented in another way, changing the psychological impact for end-users.

The above examples show that there is multitude of products and services already available today to avoid the traditional, very strict and inflexible debt products, which is still the majority of debt products sold today. These new products provide valuable alternatives, but require further promotion to become more wide-spread. They also require further packaging and guidance, so that customers are automatically directed towards the best product in line with their objectives, horizon, risk profile, knowledge and experience. For people active in the investment space this may ring a bell, as this is exactly the aim of the MiFID2 directive in the investment space: define via a questionnaire the investment profile of the customer and propose only investment products suitable to the customer’s investment profile. It is time that a similar directive in the credits space can really guide customers towards the best choice of financing for their future financing needs.